Protecting “the hijackers”

The fabled Malaysia meeting: January 2000

There is an unhealthy level of fable around a famous meeting of associates of Osama bin Laden that took place in Kuala Lumpur between the 5th and the 8th of January 2000. This was supposedly a meeting, maybe even the meeting, at which the September 11 attacks were planned in detail. Being so close to the Millennium celebrations and the security concerns that caused, the meeting is said to have worried US intelligence agencies no end. The idea here is of larger-than-life terrorists plotting dastardly deeds. But these were not supermen and it is clear the CIA, in collaboration with the Malaysian authorities, was monitoring it all pretty closely, which surely means that to a great extent they had it under control.

The CIA got wind of the planned meeting in late 1999, because the National Security Agency was listening to calls to and from the so-called al-Qaeda switchboard in Sana’a, Yemen. The switchboard, or communications hub, had been surveilled since 1996, because it was regularly called from Afghanistan by Osama bin Laden. Bin Laden called the switchboard, and instructions were then forwarded on from there. By this time, it was implicated in the bombings of U.S. embassies in east Africa that had taken place the previous year, in ’98. One of the bombers had the hub’s phone number in his pocket. So even the FBI knew about the hub at this point; not just the NSA which was already listening to the hub directly, and the CIA which was getting reports from the NSA.

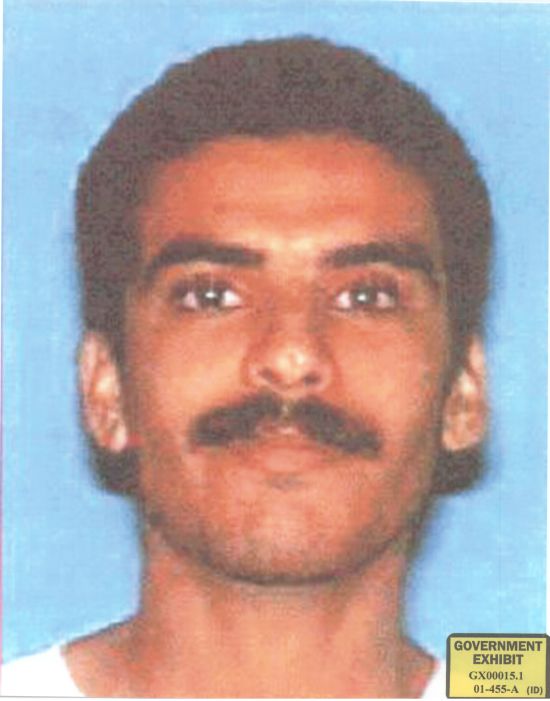

This again makes it sound like a sophisticated nexus in the bin Ladenist operation. But fundamentally it was the home of an old comrade of bin Laden’s. Also living there was Khalid al-Mihdhar, one of the future alleged 9/11 hijackers. He was married to the old comrade’s daughter. Al-Mihdhar made the trip to Kuala Lumpur. His trip was tracked, and while he was transferring through Dubai, his passport was photocopied. It contained a visa to enter the U.S.A.

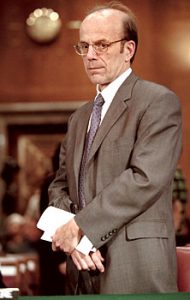

When this information was passed to the CIA’s bin Laden tracking unit, called Alec Station, it naturally grabbed the attention of Doug Miller, an FBI agent seconded there, or detailed there, in American military and intelligence parlance. So he drafted a Central Intelligence Report, or CIR, back to his FBI colleagues about al-Mihdhar’s US visa. But a couple of hours later he got an email saying “pls hold off on the CIR per Tom Wilshere”. Tom Wilshere was the deputy chief of Alec Station.

Doug Miller and Mark Rossini, the two FBI agents working at Alec Station, complained at the time about the order not to tell the FBI about the visa. After all, the FBI was tasked with operating against terrorism inside the States, where the CIA is bound in its charter not to operate. But their hands were tied, because working at Alec Station meant abiding by the CIA’s operational secrecy requirements. At the time, they were fed a line that the U.S. visa was a diversion, and that al-Mihdhar was due to be part of an attack in southeast Asia. Then an internal CIA cable claimed that the US visa information had been hand-delivered to FBI headquarters, but there is no record of anyone from Alec Station turning up there, let alone delivering important information.

“pls hold off on the CIR per Tom Wilshere”

Here is Tom Wilshere in 2002, replying to Congressman Richard Burr under oath before the Joint Intelligence Committee Inquiry. He gave the evidence behind a screen, and was only later identified as Wilshere.

Burr: At this time there was no attempt to put these individuals on the watchlist, correct?

Wilshere: That’s right.

Burr: No discussion. To the best of your knowledge, was the FBI ever notified?

Wilshere: To the best of my knowledge, the intent was to notify the FBI, and I believe the people involved in the operation thought the FBI had been notified. Something apparently was dropped somewhere, and we don’t know where that was.

An honest response from Wilshere would have mentioned that he headed that operation, that he originally ordered the visa information not to be passed on, and that if there had been an intent to notify FBI Headquarters of the U.S. visa information, there was no reason not to include the FBI in the cable saying it had been passed.

There are two things to note here, before getting into the meat and potatoes of the next 20 months leading up to 9/11. First, like all the later embarrassing incidents relating to Khalid al-Mihdhar, the withholding of the visa information was not a CIA intelligence failure: it was a decision to withhold intelligence. The bog-standard response, “Oh I’m sure mistakes happened,” won’t stand up by the end of this article. Nor will the bog-standard response that “Decisions may have been taken, but no-one could reasonably have foreseen that this would end in a terrorist attack”. Second, as we’ll see, like this visa withholding, almost all those decisions were executed, though probably not taken, by Tom Wilshere and one close colleague of his, Dina Corsi.

And that puts a different spin on another comment Wilshere made to the Joint Intelligence Committee:

As I think has become clearer through the Joint Inquiry staff, every place that something could have gone wrong in this, over a year and a half, it went wrong. All the processes that we’ve put in place, all the safeguards, everything else, they failed at every opportunity, nothing went right.

Wilshere was an accomplished liar.

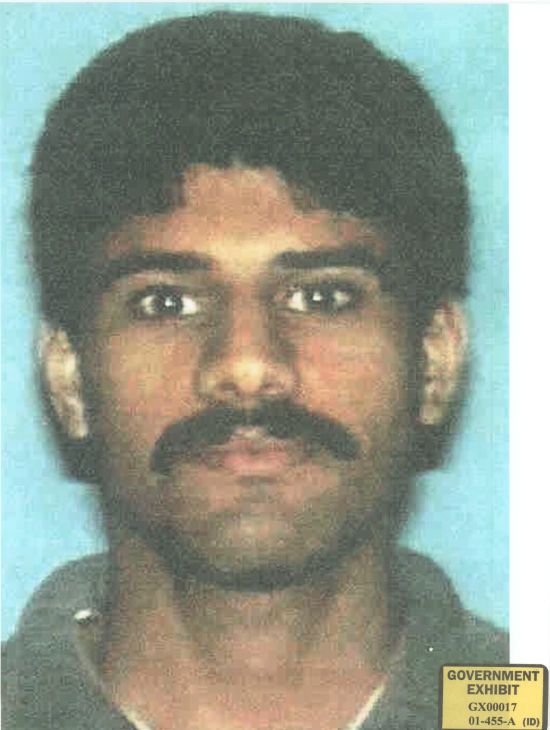

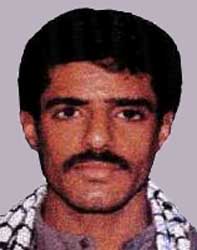

At the Kuala Lumpur meeting Khalid al-Mihdhar met up with two people critical to this story. First up, Nawaf al-Hazmi, who was his alleged fellow hijacker on American Airlines flight 77, which flew into the Pentagon. And secondly, Khallad bin Attash, who was already a suspect in the east Africa embassy bombings, because he made the martyrdom video of one of the bombers, and whom the FBI later identified as a mastermind in the U.S.S. Cole bombing that was to come in October 2000.

Apart from operating inside the United States, the FBI is tasked with carrying out with criminal investigations when there is an attack on U.S. interests outside the United States. As you can imagine, when bin Attash went from being a common or garden FBI suspect, to being a bombing mastermind, anyone who had spent any time with him became very interesting to FBI agents.

And the thing is, and what makes the Kuala Lumpur meeting so important, is that surveillance photos of al-Mihdhar, al-Hazmi and bin Attash together and separately were taken, and the way the CIA used them later on, showed that the last thing they wanted was for the FBI to make a connection between bin Attash and the future hijackers al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi.

As I have hinted, the Kuala Lumpur meeting was treated as a big deal at the time it was happening: the National Security Advisor was informed of it, for example. Many pieces of testimony suggest that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was later called the mastermind of 9/11, but was already wanted in connection with a 1997 Bojinka plot to blow up multiple airplanes over the Pacific, was at the meeting. A confirmed attendee was Hambali, the military head of the al-Qaeda affiliate in southeast Asia, known to the US through his involvement in the Bojinka plot. According to the Guantanamo Files – leaked by Bradley, now Chelsea, Manning – Hambali, who is detained there, has told his captors that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was at the meeting. While not vital to our story, it does go to show that the CIA had no problems letting wanted men wander, while keeping an eye on them. It is worth bearing that in mind.

Al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi’s excellent adventure: January – March 2000

After the Kuala Lumpur meeting, al-Mihdhar, al-Hazmi and bin Attash continued their adventure. On the 8th of January, the meeting ended, and these three men flew to Bangkok. The CIA’s Bangkok station acted very fishily indeed in monitoring the three men. It claimed it could not monitor them because it did not get to the airport in time. But in an intercepted phone call from Kuala Lumpur bin Attash had already booked ahead, at a hotel where they did stay. The CIA could have looked there, if they in fact did not.

Meanwhile in Washington D.C., the chief of Alec Station, Richard Blee, undoubtedly one of the guilty men of 9/11, was briefing his CIA superiors up till January the 14th that the Kuala Lumpur meeting was still going on. He did not tell them what Alec Station knew, that the three men had flown to Bangkok. Whether he was giving them plausible deniability in a complex operation, or genuinely keeping them in the dark – probably the first option – it does show something funny was still going on regarding al-Mihdhar, al-Hazmi and bin Attash.

The CIA Bangkok station had requested that the three men be put on the Thai travel watchlist, so it should have got the memo, and probably did, when al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi flew from Bangkok to Los Angeles on January 15th 2000. Two bin Laden associates landing in the US ought to have caused some excitement, in Bangkok and Alec Stations, but nothing is recorded to have happened. Allegedly, it was just missed, and you know, mistakes happen.

Bangkok station got a second opportunity to tell the CIA about the travel to Los Angeles early in February, when a straightforward CIA officer in Kuala Lumpur sent an inconvenient cable to Bangkok station, asking what had happened with the three bin Laden associates. Bangkok station took its sweet time, but another month later, on March 5th, it replied that “al-Hazmi and a companion”, had flown to Los Angeles. Given that they were taking this from a flight manifest, they surely knew the other guy was al-Mihdhar, but that was just another little obfuscation.

It was later reported that one CIA officer, probably the Kuala Lumpur officer who had asked about the bin Laden associates, had read the cable about travel to LA “with interest”, as he wrote, indicating he knew how important it was. It was also reported that in total 50 to 60 officers read cables about the travel of bin Laden associates between January and March, which obviously includes this March 5th cable about travel to LA. But George Tenet, the CIA director from 1997 till 2004, was out of the traps early with his explanation, which he gave while being savaged by a dead American sheep, Senator Dan Levin, whose voice we’ll hear first in this clip from 2002. Note, by the way, that Levin does not even mention the companion, al-Mihdhar.

Levin: On March 5th, the CIA learns that Hazmi had actually entered the United States on January 15th, seven days after leaving the al-Qaeda meeting in Malaysia. So now, the CIA knows Hazmi is in the United States but the CIA still doesn’t put Hazmi or Mihdhar on the watchlist and still does not notify the FBI about a very critical fact: a known al-Qaeda operative – we’re at war with al-Qaeda – a known al-Qaeda operative got into the United States. My question is: do you know specifically why the FBI was not notified of that critical fact at that time?

Tenet: The cable that came in from the field at the time, sir, was labelled “information only”, and I know that nobody read that cable.

Levin: But my question is, do you know why the FBI was not notified of the fact that an al-Qaeda operative now was known in March of the year 2000 to have entered the United States? Why did the CIA not specifically notify the FBI?

Tenet: Sir, if we weren’t aware of it, when it came into Headquarters, we couldn’t have notified them. Nobody read that cable in March, in the March timeframe.

Levin: So that the cable that said that Hazmi had entered the United States came to your Headquarters, nobody read it?

Tenet: Yes, sir. It was an information-only cable from the field and nobody read that information-only cable.

So if you want to know why I am saying that there is a lot hidden from the public, and that aggressive investigation does not happen, after listening to that you can appreciate that one reason for this is that pompous senators are too afraid to say “Yeah, right”, even when the only other explanation for their follow-up question is that they’re too thick to understand the first answer. Another is that CIA directors are encouraged by this to lie.

A pretext for mass surveillance: January 2000 – present

The usual 9/11 fable ignores, or even more bizarrely just minimises, all the evidence that the CIA tracked the alleged hijackers to the US, and concentrates on Saudi Arabian support for al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi when they got there. Briefly, it is true: they were met by a Saudi spy, Omar al-Bayoumi, who put them up for a while in San Diego, gave them money, and later put them in touch with a friend of his, who they went to live with. That guy, Abdusattar Sheikh, was actually an FBI informant, but seemingly was not asked and did not tell his FBI liaison much about his new lodgers.

By the way, what they were doing was getting flying lessons, but they were no good, and were actually known as Dumb and Dumber at their flight school, which is why they are said to have ended up as muscle hijackers on American flight 77, rather than being pilots.

During this time, it is very possible the CIA was getting information on al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi through Saudi sources, while maybe doing some monitoring on their own too. We do not know the details of what surveillance took place in the U.S. Naturally, the CIA has denied there was any. But it has lied so much that there is no reason to take that at face value. What is really important is that they were in the U.S. with the CIA’s full knowledge, and I think that allows us to posit that some form of monitoring took place.

Similarly, if 9/11 was primarily an American operation, as I tend to think, it is useful, but not of earthshattering significance, to note that tracking al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi would have led them to alleged hijackers on two other planes, who they later lived with. It would also have led them to two of the alleged pilots, who got ID’s using the same address as they went on to live at in New Jersey in 2001. Two of the people they lived with in New Jersey flew down to Florida and met some of the alleged pilots there… and so on and so on. Fundamentally, all the alleged hijackers’ security was poor and easily penetrated.

It is more interesting to note that in February 2000, the CIA rejected help from an unnamed foreign intelligence agency in finding al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi. Why would they do that, if they didn’t know where they were?

And it is critically important to note that while they were in San Diego, al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi made calls back the so-called al-Qaeda switchboard in Yemen, where after all al-Mihdhar’s wife and father-in-law lived. The landline used in these calls was registered in al-Hazmi’s real name, and the NSA had his name on a watchlist.

These calls have been the justification by President Bush, at the time of the 2005 warrantless wiretapping scandal, and by President Obama, after the Edward Snowden leaks, for suspicionless mass surveillance.

Bush: In the weeks following the terrorist attacks on our nation, I authorized the National Security Agency, consistent with US law and the Constitution, to intercept the international communications of people with known links to al-Qaida and related terrorist organizations. Before we intercept these communications, the Government must have information that establishes a clear link to these terrorist networks. This is a highly classified program that is crucial to our national security. Its purpose is to detect and prevent terrorist attacks against the United States, our friends and allies. As the 9/11 Commission pointed out, it was clear that terrorists inside the United States were communicating with terrorists abroad before the September 11th attacks. And the Commission criticized our nation’s inability to uncover links between terrorists here at home and terrorists abroad. Two of the terrorist hijackers who flew a jet in the Pentagon, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar, communicated while they were in the United States to other members of al-Qaida who were overseas. But we didn’t know they were here, until it was too late.

Obama: This brings me to the program that has generated the most controversy in the past few months: the bulk collection of telephone records under section 2.15. Let me repeat what I said when this story first broke: this program does not involve the content of phone calls, or the names of people making calls. Instead, it provides a record of phone numbers and the times and lengths of calls. Metadata, that can be queried if and when we have a reasonable suspicion that a particular number is linked to a terrorist organization. Why is this necessary? The programme grew out of a desire to address a gap identified after 9/11. One of the 9/11 hijackers, Khalid al-Mihdhar, made a phone call from San Diego to a known al-Qaida safehouse in Yemen. NSA saw that call. But it could not see that the call was coming from an individual already in the United States. The telephone metadata program under section 2.15 was designed to map the communications of terrorists so we can see who they may be in contact with as quickly as possible.

A report by a Congressional committee, the Joint Intelligence Committee Inquiry on intelligence failures prior to 9/11, which was published in 2003, says information contained in these calls between San Diego and Yemen was passed on to the FBI, the CIA and other agencies. If that is true, that means it was important stuff, because the NSA did not pass on every little trifle. But public information about what was passed on is non-existent. And according to the Joint Intelligence Committee, the NSA passed on this information without realising one half of the calls was in the U.S.

Supposedly, finding out where the calls came from was a separate and very different matter from the contents of the calls. The NSA’s excuses for not tracing these calls between San Diego and the Yemen hub have been poor and inconsistent. Bear in mind here again that by 2000 the US government had already identified the Yemen hub as critical to the 1998 east Africa embassy bombings which killed 224 people, mostly African civilians, in the vicinity of the American embassies in Dar-es-Salaam in Tanzania and Nairobi in Kenya. So the Yemen hub was a prime NSA intelligence collection target, though even at this point, before the Cole bombing, why it had not been shut down is a good question. First, the NSA merely explained to Congress that before 9/11, as a matter of policy it did not target suspected terrorists in the United States, which nonetheless it was allowed to do with a warrant, but that it regularly provided information to the FBI. That left the question why they didn’t tell the FBI about these calls. So, second, they explained in 2004 that neither the contents nor the physics of the calls suggested the other end of the calls was in the U.S.

There is a contradiction here. In one explanation, they knew one end of the calls was in the U.S., and did not follow up for that reason, and in the other they did not know the other end of the calls was in the U.S. I suppose you could say that the first answer is a recital of policy, and the second is a specific response. But the NSA – which used to be said to stand for No Such Agency – is so secretive that there is no reason to take this at face value.

What’s more, evidence was presented during the east Africa embassy bombing trial, which took place in early 2001, that calls had been traced between the Yemen hub, and Kenya, Afghanistan and many other places around the world. But not America? One is inclined to say, pull the other one. We do not know exactly what the relationship was between the CIA’s protection of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi in the US, on the one hand, and the NSA’s failure to tell everyone about their phone calls to Yemen, on the other. (Evidence contained in Ray Nowosielski and John Duffy’s book, The Watchdogs Didn’t Bark, does suggest there may have been a tandem operation.) But we do know that the popular justification for mass electronic surveillance, right to the present day, is a lie about al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi.

Silence, stalling and fishing trips: June 2000 – Summer 2001

Here is an important wrinkle in the story: Nawaf al-Hazmi stayed in the States until 9/11, but Khalid al-Mihdhar left again, from June the 10th, 2000 until he returned on Independence Day, of all days, in 2001.

What was he doing? Well, he is supposed to have been involved in assisting the muscle hijackers travel to the U.S., which required a lot of toing and froing between Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan. But he is also alleged to have been involved in the attack on the U.S.S. Cole, which took place off Aden Harbour, in Yemen, on October 12th 2000, killing 17 American sailors.

Whatever about direct involvement, there is no doubt al-Mihdhar was circumstantially linked to it. A U.S. investigator said after 9/11 that the Yemen hub, which after all he lived in, had been used by the Cole bombers “to put everything together”, which probably means in organisational, rather than bomb-making terms. And the FBI found out shortly after the Cole bombing that it was a rerun of an unsuccessful attack on the U.S.S. The Sullivans, which failed on January 3rd 2000, when the boat supposed to carry the bomb to the US ship sunk as soon as it was due to set off because the bomb was too heavy. Just as al-Mihdhar left for Malaysia very shortly after the attempt on U.S.S. The Sullivans, he is said to have departed from Yemen very shortly after the U.S.S. Cole attack.

Above all though, al-Mihdhar was linked to the Cole through his association with Khallad bin Attash, who we’ve already come across as an attendee at the January 2000 Kuala Lumpur meeting, and who flew from there to Bangkok with al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi. After the Cole attack, the FBI identified bin Attash as one of its two masterminds. As I have already noted, that naturally made anyone associated with him of great interest to the Bureau. And that would have included al-Mihdhar.

The FBI agents who investigated the Cole attack came to suspect that a meeting of bin Laden associates had taken place somewhere in southeast Asia in January 2000. Under interrogation by Yemeni authorities, Fahd al-Quso, who had been involved, admitted that he had met bin Attash at that time in Bangkok, and given him money. So the FBI’s lead Cole investigator, Ali Soufan, asked the CIA during November 2000 what it knew about a meeting around that time and place, and the CIA said, “Nothing!”

When Soufan himself interrogated al-Quso, he found out the name of the hotel the men had stayed at in Bangkok, and checked its telephone records, which revealed calls between it and a payphone outside the apartment where the Kuala Lumpur meeting was held. So he asked the CIA again in April 2001, and again they said they knew nothing. And it was the same when he made his last, even more specific, request for information in July 2001.

Anyone associated with Khallad bin Attash was of great interest to the Bureau.

And all this had the effect of preserving the CIA’s exclusive hold over al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi, its use of them as assets or sources, witting or not. Lawrence Wright, the journalist for the New Yorker who wrote about Soufan’s requests for information, frustratingly does not specify who dealt with the requests, but logically it must have been Alec Station, who specialised in associates of bin Laden. Tom Wilshere and other officers who had already kept the FBI in the dark about al-Mihdhar’s visa must surely have been in the loop.

Soufan’s requests, which could have led the Cole investigators to al-Mihdhar and to al-Hazmi, who was still in the U.S. all this time, in a few hours, have never been reported on in any declassified government report: not The 9/11 Commission Report, not the Department of Justice Inspector General’s report on how FBI employees handled intelligence before 9/11, not the Joint Intelligence Committee report on pre-9/11 intelligence handling. But in fact, it’s likely that an account in the original version of Department of Justice Inspector General’s report, which is by far the most detailed of them, remains classified, despite there being no continuing reason of security for the classification. Soufan’s requests for information about a meeting in southeast Asia are too damning.

The way that the CIA, throughout the course of 2001, used and abused the surveillance photos of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi taken in Kuala Lumpur the previous year is further evidence of its bad faith. Essentially, on two occasions, CIA officers showed individuals associated with the FBI photos of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi in order to check whether they could identify the alleged future hijackers. These can be thought of as fishing trips.

The CIA’s first fishing trip, in January 2001, was with an informant based in Islamabad, used by both the CIA and the FBI. What happened is pretty farcical. The Department of Justice account is that there was speculation between CIA officers that al-Mihdhar and bin Attash were the same person. Now, this speculation was ridiculous, and certainly not sincere. The CIA knew enough to know that bin Attash only had one leg, for example, and they didn’t look very much alike facially. Tellingly, the speculation wasn’t shared with the Bureau, because it was too off the wall.

So, with no Bureau agent present, a CIA officer in Islamabad showed two pictures to the source, based on this speculation. The farcical part is that the source did not recognise al-Mihdhar, but wrongly identified Attash from the al-Hazmi photo. So now the CIA had to take heed of the possibility that the source would identify Khallad bin Attash to the FBI as having been with the two travellers to America at Kuala Lumpur. But of course it did not tell the FBI that the source, wrongly from the photo, but rightly in fact, had identified bin Attash, the object of so much of the FBI’s time and attention, as having been at Kuala Lumpur.

The second fishing trip happened on June 11, 2001. Tom Wilshere had actually transferred the previous month from being deputy chief of Alec Station to working as a CIA liaison at FBI Headquarters, in the International Terrorism Operations Section. Nominally, he was supposed to help the FBI where it needed the CIA’s assistance. In practice, as we’ll see in the rest of this podcast, he was there, with the ready co-operation of a number of officials in FBI Headquarters, as a mole, as a saboteur and a blocker of the efforts of FBI agents in the field to investigate the Cole attack, which would have led them to al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi’s travel to the U.S.

Again, this second fishing trip began with another speculation that seems insincere. What happened was that Wilshere and another CIA officer, Clark Shannon, started to speculate in emails about Fahd al-Quso, who as we’ve already seen was a low-level operative in the Cole attack, who had been arrested and interrogated by Ali Soufan, and had admitted giving money to bin Attash in Bangkok in January 2000. What contacts, Wilshere and Clark Shannon asked each other, had al-Quso had with other Cole attackers? Wilshere had obtained three photos from the Kuala Lumpur operation and now gave them to Dina Corsi, an analyst in FBI Headquarters, whose job was supposed to be to assist the Cole investigators. But again, none of the three photos were actually of al-Quso, but were actually of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi.

Now, if Wilshere and Shannon wanted to know if Fahd al-Quso had attended the Kuala Lumpur meeting, they would have got all the Kuala Lumpur photos and shown them to FBI agents, one of whom, Ali Soufan, had already interrogated him in Yemen. They would not have just have given Corsi pictures of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi. Anyway, Corsi and Clark Shannon went to New York for this meeting on the 11th of June 2001, exactly three months before 9/11. The FBI Cole investigators were based there, because all bin Laden-related terrorism had been investigated from New York, ever since the World Trade Center bombings in 1993. Corsi and Shannon asked two of the Cole agents if they recognised anyone in the photos, and whether they recognised al-Quso in the photos. One of them tentatively said that al-Quso might be there, and then the FBI agents asked some straightforward questions: who was in the photos? why and where were they taken? were there other photos? and what was their connection to the Cole attack?

Corsi and Shannon were not there to be forthcoming, and the meeting descended into what was later described as a “shouting match”. Under heavy pressure, Corsi did give them al-Mihdhar’s name, and Shannon told them al-Mihdhar was travelling on a Saudi passport. But the Cole investigators weren’t told what would have meant something to them: that the picture was taken in Kuala Lumpur, and bin Attash was there at the time. All they knew was that Corsi and Shannon were hiding something from them. Incidentally, Mark Rossini describes the June 11 meeting as being when the CIA asked the FBI to help find al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi. But all the evidence is to the contrary. Tom Wilshere’s subsequent actions, and Dina Corsi’s in close co-operation with Wilshere, make it clear that all they were looking to find out was: did the Cole investigators recognise al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi? All the investigators knew now was, they needed to know about them:

Burr: On June the 11th, 2001, the CIA went to the New York Office of the FBI, and in fact passed on [photos of al-Mihdhar] to New York agents who led the Cole investigation, am I correct?

Bongardt: Yes, sir.

Burr: Again, these photos were shown and discussed. The records show that Mihdhar’s name did come up, yet we’re unclear in the context that it came up. Can you help to clarify that for us?

Bongardt: Yes, sir. When these photos were shown to us, we had information at the time that one of our suspects [Fahd al-Quso] had actually travelled to the same region of the world [Kuala Lumpur] that this might have taken place, so we pressed the individuals there [at the New York meeting] for more information regarding the meeting. Usually what I’ve found is, coincidences don’t occur too much in this job. Usually, a lot of times, when things are the way they are, it’s because that’s pretty much the way they are. So we pressed them for information. Now, the other agents in the meeting recall, um – one agent does not recall the name being given up in the big meeting. There were numerous sidebars that happened. Regardless of that, at the end of that meeting – someone would say it was just because I was able to get the name out of the analyst – but at the end of that day we knew the name Khalid al-Mihdhar, but nothing else [emphases added].

So in the months following the June 11th meeting – throughout June, July, and August – one of the New York FBI agents who was there, Steve Bongardt, kept asking Dina Corsi, the analyst, for information about al-Mihdhar. Here is how he described it at the Congressional Inquiry:

In fact I’d had several conversations with the analyst after that, because we would talk on other matters, and almost every time I would ask her, ‘What’s the story with the Mihdhar information? When’s it gonna get passed? Do we have anything yet? When’s it gonna get passed?’ And each time I was told that the information had not been passed yet, and the sense I got from her, based on our conversations, was that she was trying as hard as she could to get the information passed, or at least the ability to tell us about the information.

What was the information Bongardt should have got from Corsi? There were at least two, possibly three, big things.

Number one, Bongardt should have got copies of the photos he was shown at that meeting. Corsi had not let him keep the copies shown at that time, for absolutely no good reason at all. Her explanations after 9/11 reflect the fact that there was no reason not to give Bongardt the photos. On the one hand, she said that despite Wilshere having given her the photos, they had still not been “formally passed” to the FBI; when Wilshere was asked about this, he dished her on this, saying there was no problem with passing it on inside the FBI, although I think we can safely he would not have been happy with the investigators having them at the time. So her second explanation was the investigators could not show them to the Yemeni authorities working on the Cole. Fine, but that should not have stopped her giving them to the FBI investigators. This was bad faith on Corsi’s part.

Number two, another piece of information Corsi should have given Bongardt was those NSA cables about al-Mihdhar from late 1999, which, again, linked al-Mihdhar to the Yemen communications hub, which was very important, and said that he was due to go to Kuala Lumpur, which was critically important. Corsi had read these NSA cables. Her explanation for not passing them on, again, does not pass muster. To pass them to FBI criminal investigators, she needed the approval of the NSA general counsel, American parlance for the NSA lawyers. So that was her excuse. But there are problems with it. For one thing, while approval was needed for criminal investigators on the Cole case, no approval was needed for intelligence agents associated with the Cole. As in many investigations including in Ireland and the UK, there were designated officers who were free to receive all kinds of information, which they could then decide either to pass on, or not, to criminal investigators, depending on whether it might prejudice the investigation. There had been an intelligence officer at the June 11th meeting, but if Corsi was unaware of that, she was certainly aware that there were intelligence officers associated with the Cole case. The Department of Justice inspector general’s report actually makes an excuse for Corsi, saying that getting the lawyers’ approval involved “lengthy procedures.” But as we’ll hear later, when she did later seek that approval in very suspicious circumstances, it only took a day. The stalling was deliberate.

The possible third piece of information that Bongardt should have received from Corsi was the identification of Khallad bin Attash at Kuala Lumpur in January 2000. I say “possible” because it is not actually clear when Corsi learned that the Islamabad source had identified bin Attash as having been there. But an email she wrote on August 22nd shows she was aware of it by then. There was a meeting on May the 29th, which was attended by Dina Corsi, Clark Shannon, the CIA analyst, and Margaret Gillespie. They all later claimed not to recall anything about the meeting. Not telling Cole criminal investigators about the identification of the mastermind was a big deal, and worth forgetting, so this meeting may have been when Shannon told Corsi. Equally, Wilshere could have told her about it during lunch break in FBI Headquarters. At any rate, Corsi herself, an FBI analyst and not just the CIA, hid this information from the FBI agents to whom it was so important.

Incidentally it is fair enough to wonder: why did Corsi act as if when Wilshere asked her to jump, the only question in her mind was, How high? And how did Wilshere carry such sway at FBI Headquarters?

One clue is that the chief of the International Terrorism Operations Section, Michael Rolince, was a friend and colleague of Wilshere’s, and described him admiringly at the Congressional Inquiry: “Before I begin my prepared remarks, I would just like to say for the record that I am honored and proud to follow an individual with whom I worked closely for the last several years, and whom I consider to be one of the finest counterterrorism experts in the world.” There was no contradiction necessarily between having a job with Rolince as her boss, and doing whatever Wilshere wanted her to do. More broadly, whatever the motive, what matters really is the actions, and actions speak louder than words.

Just before he moved to being Alec Station’s mole in the International Terrorism section of the FBI, in May 2001, Tom Wilshere instigated a little stalling too. By the way, when considering the reason for his move to the FBI, the fact that Ali Soufan had been making increasingly specific requests for information about the Kuala Lumpur meeting might have been relevant. Trying to keep him off the trail would have been a good enough reason to transfer.

What Wilshere did on May 15th, shortly before leaving for the FBI, was review the cables sent around the time of that Kuala Lumpur meeting. So he reread the cable about al-Mihdhar’s US visa, and the cable about the travel of al-Hazmi and a companion, clearly al-Mihdhar, to Los Angeles. And what he didn’t do, after reading these, was place the two men on a watchlist, or tell the FBI about them. The excuse he offered is indirectly quoted in the 9/11 Commission Report, in which Wilshere is referred to by the alias, “John”:

Despite the US links evident in this traffic ‘John’ made no effort to determine whether any of these individuals was in the United States. He did not raise that possibility with his FBI counterpart. He was focused on Malaysia. John described the CIA as an agency that tended to play a zone-defense. He was worrying solely about Southeast Asia, not the United States.

As you might remember, Malaysia had been where the next attack had been supposed to happen in January 2000, when Wilshere first blocked the U.S. visa information about al-Mihdhar. In the meantime al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi had travelled to the U.S., possibly just for some rest and relaxation, and then Cole bombing had happened in Yemen. So the Malaysia excuse was not a good one, and all the more unbelievable given that he was about to start working at the FBI, primarily a domestic agency.

Instead of telling the FBI about the travel of al-Hazmi and a companion to the U.S., what Wilshere did was assign Maggie Gillespie, an FBI analyst and detailee in Alec Station to review those files again. Or rather, he told other managers at Alec Station to give her that assignment, while he was getting ready to vamoose into the FBI. By teeing up a second review, he was effectively setting up an excuse for his own inaction. Not a good one, but given the weakness, in fact, the probable cowardice, of the post-9/11 investigations, more than good enough, as it turned out.

Now, there was a bit of a difference between Gillespie and the other FBI detailees, as Mark Rossini points out: “The Agency people loved her. Maggie was treated from the beginning like a CIA employee. I mean, she wrote CIRs, she wrote TDs and TDXs [telegraphic disseminations, and external telegraphic disseminations]. She actually got the ticket, if you will, on a case or a subject and followed it. So Maggie was treated – well of course, it was all women too. Doug and I were like the only two guys there, really, besides Rich and Wilshere.” And as Steve Bongardt pointed out more generally, there was always another danger with detailees: “Once an individual goes to the FBI or vice versa, that individual becomes beholden to that institution that they’re going to.” Basically, Margaret Gillespie was on side, and that is how she acted. Whereas Wilshere read the cables about the U.S. visa and the U.S. travel on one day, Gillespie’s so-called review panned out very differently.

For one thing, Wilshere told her to give it a low priority, to do the research in her free time. Gillespie elaborated on this by saying that her main priority was Yemen, where it was feared that U.S. personnel who had been drawn there after the Cole bombing might come under a follow-up attack. But given that this review was intended to find details about where the next attack might happen, you might think it would have gone faster than it did.

Here’s how it went in any event: early in June 2001, Gillespie looked at an information database called Intelink, which the CIA shared with other agencies in the Intelligence Community, including the FBI, and she didn’t look at Hercules, an internal CIA database, which contained information the FBI didn’t have, such as the NSA cables about al-Mihdhar’s travel to Kuala Lumpur. So she could be guaranteed not to learn anything currently being sought by the FBI’s Cole investigators.

Some day in the second half of July 2001 – so, again, this is about two months after she was given the assignment – Gillespie found a cable referencing al-Mihdhar’s possession of a U.S. visa, and very conveniently on the same day also found the cable saying the visa information had been hand delivered to FBI Headquarters, so there was no need to follow up on it.

And then, happily, on August 21st, three weeks before 9/11, Gillespie looks at the March 5th 2000 cable, about the travel of al-Hazmi and a companion, who she was quickly able to identify as al-Mihdhar, to Los Angeles, and she finally let the Immigration and Naturalisation Service, and the FBI, know these two bin Laden associates were in the country. Her explanation for this was that after slowly looking at the information over the course of four months, at this point, “it all clicks for me”. But Gillespie had been actually copied in to correspondence between Wilshere and another CIA officer about the travel to Los Angeles in May 2001, so why didn’t it click for her then? Why had it allegedly not clicked for Wilshere at that time either?

Even if Gillespie didn’t read about the alleged hijackers’ U.S. travel then, all the evidence points against this having been a real cable review. There is the length of time it took, when it was completed by Wilshere in a day. There is the fact that she was working with Wilshere, who demonstrably was already hiding information about al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi from the FBI. And frankly, there is the suspiciousness of the date, shortly before 9/11. She was also not a reliable witness, claiming she was not aware in January 2000 of the Kuala Lumpur meeting, despite having accessed cables about it at the time.

As the Department of Justice account puts it, using Maggie Gillespie’s pseudonym, Mary, in its report, and I do not think we should discount the possibility of an ironic tone here: “We question the amount of time that elapsed between Mary’s assignment and her discovery of the important information. As we discussed previously, however, Mary’s assignments were directed and controlled by her managers in the CTC.”

And here is Tom Wilshere’s convoluted description of Gillespie’s review:

There was a miss in January, there was a miss in March. We’ve acknowledged that. What happened after that was, I think, in part a function –… Stuff like that should normally emerge during the course of a file review, if something provokes the file review. Once that file review is provoked, the information is readily recoverable. ‘That’s how I found what I found when I found it’ kind of thing. But the story kind of emerged in dribs and drabs because there was no one person who reconstructed the whole file.

No mention, again, that he caused the so-called “miss” in January. No mention that he gave Gillespie the assignment. No mention that he read all the relevant cables just before giving her the assignment, and could have just handed them to her. And there was one person who reconstructed the whole file, and it was Wilshere.

Incidentally, given how flimsy the excuses seem, I suppose it’s possible a listener might perversely think, the excuses are so bad, there wasn’t anything wrongdoing really: and that they were clearly just idiots. Or that I am making a mountain out of a molehill. But they were doing wrong, terrific wrong; and the reason their excuses were bad, is because there were no good ones.

Tom Wilshere’s critical, self-incriminating emails: July 2001

You may be thinking in all this: look, these sound like very irresponsible actions, hiding al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi was undoubtedly selfish and illegal from the perspective of 2000 and early 2001, and tragic from a post-9/11 perspective. But where’s the beef? Where do we get from all that, to: certain CIA officers were content to let September 11 happen?

Well, all that becomes clear from July 2001 onwards.

That July, Tom Wilshere wrote three strange emails. He was detailed to the FBI, but he wrote them back to Alec Station and the CIA’s Counterterrorist Center generally, and it’s as likely that he wrote them in Langley, CIA headquarters, as at J. Edgar Hoover building, where the FBI were headquartered. Doubtless, he wrote more than these three emails, but these are the ones on the public record, and what they do, is damn him, and his boss Richard Blee, the chief of Alec Station, out of Wilshere’s own mouth.

The first of them was sent on the 5th of July, which was the day after al-Mihdhar returned to the United States, after his thirteen-months of journeying between Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan. That may or may not be a coincidence. Here is how this July 5th email is described in the Department of Justice Inspector General’s report:

He wrote that there was a potential connection between the recent threat information and information developed about the Malaysia meetings in January 2000. In addition, he noted that in January 2000 when al-Mihdhar was travelling to Malaysia, key figures in the failed attack against the U.S.S. The Sullivans and the subsequent attack against the U.S.S. Cole also were attempting to meet in Malaysia. Therefore, he recommended that the Cole and Malaysia meetings be re-examined for potential connections to the current threat information.

First of all, it’s worth unpacking that the key figures in the attacks on U.S. ships are Fahd al-Quso, who failed to get to Malaysia because he lacked a visa; and above all to Khallad bin Attash. So, a connection is being made here between bin Attash and al-Mihdhar. Second, the recent threat information didn’t just relate to Malaysia, but to the United States. Lawrence Wright, the New Yorker writer, wrote in The Looming Tower, that Wilshere “was privy to the reports that al-Qaeda was planning a ‘Hiroshima’ in America.” Third, what would be found if the Malaysia meetings were re-examined, the way Wilshere said they should be? The information about al-Mihdhar’s U.S. visa, which Wilshere originally sat on; the U.S. travel information, which 50 CIA officers had read; all of which he had read again in May 2001. So, what is really going on here is something like this: Wilshere knows Margaret Gillespie’s so-called cable review, is a delaying tactic. In fact, he writes about it as if it didn’t exist. Which in reality it didn’t. And he’s nervous, specifically about al-Mihdhar, who he names, and he’s indirectly referring to cables about al-Mihdhar’s travel to the U.S., which is a long way from Malaysia.

Wilshere’s second July email was sent on the 13th of July. He began the email by saying: “OK. This is important,” and went on that he had just read the cable from January 2001, in which it was reported that the source in Islamabad had identified Khallad bin Attash in the January 2000 Kuala Lumpur photos. Khallad, he said, is a “major league killer who orchestrated the Cole attack and possibly the Africa bombings.” Again he recommended looking at the Malaysia meetings, without mentioning the al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi travel information which were the most interesting things about it. And he finished up by asking Counterterrorist Center managers, “Can this information be sent via CIR to the Bureau?” That’s Central Intelligence Report, in case you’ve forgotten.

Now, there is a lot that is interesting here. He’s asking his CIA colleagues to tell the FBI that bin Attash was in Malaysia, but after 9/11 the CIA claimed it had given the FBI that information as soon as the identification was made, in January 2001. After all, the CIA said, the source in Islamabad who made the identification was a joint source, used equally by the two agencies. But that CIA claim was just a normal lie, I guess. Another thing, as I already mentioned, is that while bin Attash had indeed been at the meetings in Kuala Lumpur, the Islamabad source had actually identified him wrongly from a photo of al-Hazmi, just a farcical mistake. Now, Wilshere knew which photos had been shown to the Islamabad source, so after the identification from those photos happened, he said “someone [i.e. the Islamabad source], someone saw something that wasn’t there”. Effectively, he knew Khallad’s face better than that source. But now he is saying it’s important that the identification of Khallad, even from the wrong photo, be sent to the Bureau, because what’s important is the information that would lead them to know about the meetings, and ultimately to tracking down al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi. And again, he is recommending a cable review, which he had already informally assigned to Maggie Gillespie, but isn’t happening.

By the way, one of the recipients of this July 13th email was Richard Blee, the chief of Alec Station. That is what you would expect, given that he was Wilshere’s boss and Wilshere was asking for something to happen. But the point is that the names of the recipients of these emails generally weren’t mentioned in the reports. In this case, though, the 9/11 Commission Report notes that Blee referred to Wilshere’s email in another email to a colleague on the same day. Except on the whim of the post-9/11 investigators, we do not know who knew what when. But this time we can be certain Blee took stock of the request. Blee did not respond to Wilshere’s request to let the FBI know about the identification of bin Attash.

“Khalid Midhar should be very high interest anyway…”

We can also say that Blee received and saw the most important document about the Alec Station’s protection of the alleged hijackers, the last of Tom Wilshere’s July emails on the 23rd of the month. Blee saw it because was a follow-up to the 13th of July email, and he acknowledged further correspondence about it. If you want to understand why it is possible to say that Tom Wilshere and Richard Blee were running an operation involving al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi that they knew would assist a terrorist attack, you need to take deeply into your head and heart Tom Wilshere’s July 23rd email. Fortunately that is not rocket science. Here is how it was described in a document presented as evidence in the post-9/11 trial of Zacarias Moussaoui:

John e-mailed a CTC [Counterterrorist Center] manager inquiring as to the status of his request to pass information to the FBI. In the e-mail, John noted that “When the next big op is carried out by UBL hardcore cadre, Khallad will be at or near the top of the command food chain – and probably nowhere near either the attack site or Afghanistan. That makes people who are available and who have direct access to him of very high interest. Khalid Midhar [sic] should be very high interest anyway, given his connection to the [redacted].

There are a number of possibilities regarding what the redacted section could be. It could be a reference to the Cole attack itself, which he could be linked to independently of bin Attash. It could be a reference the Yemen communication hub, where he lived. It could even be a reference to his previous U.S. travel.

Whatever about the redaction, what Wilshere is saying in the email is that he believes al-Mihdhar is of “very high interest” in connection with the “next big op.” And, given the fact that he is saying that bin Attash will not be at the attack site, the implication is that al-Mihdhar will be, that he will be directly involved in the next bin Ladenist attack. As far as the official 9/11 story goes, he was right about that. We will see why this means we can say with no doubt that Tom Wilshere facilitated the September 11 attacks, when we come to the time after August 21st 2001, when, as I have already mentioned, Maggie Gillespie officially discovered that al-Mihdhar was in the United States, and Wilshere officially learned this the following day.

Incidentally, apart from its explosive content, a significant clue that this July 23rd e-mail is important was the fact that for years after 9/11 it did not appear in the various government reports on 9/11: not the 2002 Congressional Inquiry, not the 9/11 Commission Report, which was published in 2004, and not the unclassified version of the Department of Justice Inspector General’s Report on the FBI’s handling of intelligence before 9/11. As I mentioned briefly, it only came into the public domain during the trial of Zacarias Moussaoui, in 2006. And it was introduced as evidence by the defence.

Very briefly, Moussaoui was arrested in August 2001, and was in custody during the attacks. Apart from being accused of planning a second wave attack after 9/11, he was accused of withholding information that could have prevented 9/11. So a large part of his lawyers’ work, in making sure that Moussaoui avoided the death penalty, was showing that the government had lots of other ways to prevent 9/11. The July 23rd email was naturally quite useful to them, because it showed Tom Wilshere had predicted the identity of one of the supposed hijackers.

Rather than have Wilshere testify in court, a document was prepared, and signed off on by the prosecution and defence, called the “Substitution for the testimony of John,” which includes the 5th of July email, the 13th of July email, and the story of Wilshere’s assigning the cable review to Maggie Gillespie, all of this in exactly the same language as the Department of Justice Inspector General’s report on the FBI’s pre-9/11 handling of intelligence, which was one source used by Moussaoui’s defence. But the substitution for Tom Wilshere’s testimony also includes the July 23rd email. So it is a fair bet that the July 23rd email is in the classified version of the IG report, and was specifically excluded from the unclassified version. That goes some way to showing how important it was.

When I read these emails, I cannot decide what to think about what Tom Wilshere intended by them. The emails are so damning, in the light of his subsequent actions, that I tend to believe the real whiff of fear coming off them. Seeing as he foresaw an attack happening, he was probably worried he would be blamed, given all the withholding of important information he had demonstrably been involved in. He may have started to foresee the consequences of just following orders. On the other hand, it is possible he felt certain there would be no accountability – if only because that would entail accountability for everyone else in the CIA. And it is possible he was just writing these emails to look good. In that he succeeded. During the Congressional Inquiry on pre-9/11 intelligence, he was praised for writing the 13th of July email. Congressman Richard Burr had this to say about Wilshere:

On July the 13th, I think it was an important day, because in fact our CIA officer [Wilshere] began to put some of the pieces together that had bugged him. And that led to finding some of the lost cables, or the misfiled cables. That led to decisions, decisions that did put people on watchlists, decisions that begin the ball rolling towards an all-out press by the Bureau to look for individuals that, for numerous reasons, we had not been able to raise to this profile at that time.

But whether he was happily facilitating an attack or not, it is again demonstrably the case that in August 2001, after Maggie Gillespie told Dina Corsi in the FBI, who we’ve already seen is unreliable, that al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi were in the United States, that Wilshere oversaw all the actions that meant that the FBI Cole investigators could not arrest them. We will come to the details shortly. But he was there for that, and he was responsible. He did continue to follow orders, despite his worries and the protestations in the July emails. We do not need to know what was going on in his head, to know that actions speak louder than words.

The last thing to consider, when thinking about Tom Wilshere’s panic about al-Mihdhar in July, that he would be involved in the “next big op” is where they thought that might be. And we have seen Wilshere claimed to Mark Rossini and Doug Miller during the Millennium period, and to investigators after 9/11, that they thought there might be an attack against US interests in southeast Asia, probably Malaysia, and that Wilshere was not specifically concerned about an attack in the territorial United States.

But there is no reason to believe this, given Wilshere’s reading about the U.S. travel in May, and also given the fact that the Cole bombing had happened in Yemen. What’s more, Rich Blee, Wilshere’s boss, was giving different briefings when meeting his superiors: the primary target he claimed to be worried about was Israel, but also about other US targets around the world. If Wilshere, who had been Blee’s direct subordinate, was so adamantly worried about Malaysia, this should have turned up in the briefings. According to the famous Bob Woodward in his book State of Denial, together with follow-up reporting after that book’s release, Blee knew there was a good chance of an attack in America. On July 10th Blee and his CIA bosses rushed to the White House, one of a very few times the CIA director George Tenet did this in his seven years in the job. And Blee opened this emergency briefing by saying: “There will be a significant terrorist attack in the coming weeks or months!” He said that the attack could be spectacular, and happen simultaneously at multiple locations, and that it could be inside the US. And in his memoir Tenet wrote about the high threat environment in the summer of 2001, and specifically about a briefing given by Blee, who he called Rich B.:

Imagine how we felt at the time living through it. And imagine how I and everyone else in the room reacted during one of my updates in late July when, as we speculated about the kind of attacks we could face, Rich B. suddenly said, with complete conviction, “They’re coming here.” I’ll never forget the silence that followed.

Effectively, that silence lasted until September 11. Al-Mihdhar had arrived back in the States on July 4th. Wilshere had sent Blee a flurry of e-mails about him that month, a coincidence of one kind or another. Al-Hazmi had entered the country in January 2000, which the CIA officially knew about two months later, but most likely as it happened, and by July 2001 he was living with some of the alleged future hijackers. As Kevin Fenton’s excellent book, Disconnecting the Dots about Alec Station’s handling of the hijackers says: “Blee had good reason to say ‘They’re coming here.’ They were already here.”

‘The Wall’, analysing a poor excuse for not preventing 9/11: August 2001

As we’ve seen, Alec Station’s protection of the alleged hijackers had already undergone a number of crises. Just for example: Doug Miller’s draft cable to the FBI in January 2000 about al-Mihdhar’s U.S. visa meant he had to be ordered not to send it, so there was an incriminating email saying “pls hold off” on sending it. From January 2001 onwards, the CIA had to hide the identification of bin Attash as having been in Malaysia the previous January. And there was Steve Bongardt’s pressure for information about al-Mihdhar since the June the 11th meeting.

There was a final serious crisis in late August 2001. On August the 28th, Steve Bongardt was accidentally forwarded Dina Corsi’s email to the New York FBI office saying that al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi were in the United States, and an intelligence investigation ought to be commenced. By the way, as you can see, Corsi had taken four working days after she found out that these bin Laden associates were in the country before beginning to organise an investigation. So even if she wasn’t convinced the way Tom Wilshere was, that al-Mihdhar would be involved in the next terrorist attack, she was still taking her time. Anyway, Bongardt recognised al-Mihdhar’s name, and the crisis began when Bongardt said he wanted in on the investigation, as a Cole case criminal investigator.

Bongardt wanted the investigation into finding al-Mihdhar to be a criminal investigation, specifically a sub-file to the Cole investigation. Al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi could have been arrested as material witnesses in the Cole case. Corsi actually said he would be fired if he didn’t delete the email from his account. He did delete the email but obviously that didn’t shut down the argument.

Apart from allowing Bongardt to be involved in the investigation, what was at stake, much more importantly, in having a criminal investigation to find the future alleged hijackers was that for bureaucratic reasons it would allow the New York FBI assign more agents to the investigation. Also, the investigative tools that a criminal investigation allowed, like grand jury subpoenas, were much quicker and easier to use than intelligence investigation tools like National Security Letters.

The reason Corsi gave for saying it had to be an intelligence investigation was that the information that led the FBI to the hijackers had come from intelligence channels, the CIA and the NSA. Specifically this was a reference to the CIA’s early 2000 cables about their travel, and also the late 1999 NSA cables about al-Mihdhar’s travel to Kuala Lumpur. Therefore, Corsi argued, restrictions on giving intelligence to criminal agents applied. After 9/11, this supposed barrier on using intelligence sources in criminal investigations became famous. The conventional wisdom says that the FBI got its interpretation of the rules wrong. Although she is rarely specifically mentioned, the conventional wisdom says Dina Corsi got her interpretation of the rules wrong. And this became the standard, lazy explanation right up to the present day for why the FBI didn’t catch al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi in the days before the attacks. The official MI5 historian, Christopher Andrew, repeats it without question in his history of intelligence, The Secret World, published in 2018. The idea was that the FBI misinterpreted a real set of rules, called the “Wall”, which did put certain restrictions on sharing intelligence with criminal investigators. The idea that an honest misinterpretation of the “Wall” prevented the arrest of the hijackers is among the biggest barriers to understanding how 9/11 was enabled. So we need to look at what the “Wall” really was.

First off, just to recap, the “Wall” was a set of internal FBI regulations governing the sharing of a specific type of intelligence with criminal investigators. It arose after the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, called the FISA Act, was passed in 1978. As its name suggests the FISA Act regulated the surveillance of people in the United States in cases where there was no reasonable suspicion that a crime had been committed, no “probable cause” that a crime had been committed, as the U.S. Constitution puts it. But instead where the FBI believed someone was the agent of a foreign power, and sought a surveillance warrant for that reason. Occasionally though, evidence of a crime was found during investigations carried out using FISA warrants. At trial, defence lawyers always asked for this evidence to be thrown out, as it had been obtained using a warrant that was easier to obtain. Judges always denied these requests. But nonetheless, but 2001, information gathered under FISA warrants had to be approved by a federal prosecutor to be passed to FBI criminal agents.

You will have to forgive that digression, because as you will have noted, none of the information on which the alleged hijackers’ arrest and prosecution could be based, had been obtained under a FISA warrant. It had come from the CIA and the NSA. A footnote in The 9/11 Commission Report sums up the whole picture this way:

There was no broad prohibition against sharing information gathered through intelligence channels with criminal agents. This type of sharing occurred on a regular basis in the field. The FISA court’s procedures did not apply to all intelligence gathered regardless of collection method or source. Moreover, once information was properly shared, the criminal agent could use it for further investigation.

In fact the guidelines on FBI foreign intelligence operations said that whether a FISA warrant was being used or not, if there was a reasonable indication that a crime had been or even might be committed, federal prosecutors had to be notified, who would then inform criminal agents. Even apart from their connection to the Cole attack, the mere presence of al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi, two bin Laden associates, in the U.S. in a time of high threat could be taken as evidence that a crime might be committed.

So on the same day he found out that they were in the U.S., August 28th, Steve Bongardt asked for a lawyer’s advice about the “Wall”, which he saw with crystal clarity did not apply. He also saw how important the issue was. It’s worth quoting an email he sent to Corsi at this time. By the way Title III is the name of the usual warrant for electronic surveillance when there is reasonable suspicion in relation to a crime. Here is Bongardt’s email, some of which he read to the Joint Intelligence Committee:

Dina – where is “the wall” defined? Isn’t it dealing with FISA information? I think everyone is still confusing this issue. I know we have discussed this ad nauseam but “the wall” concept grew out of the fear that a FISA would be obtained as opposed to a Title III. Whatever happened to this – someday someone will die – and wall or not – the public will not understand why we were not more effective in throwing every resource we had at certain ‘problems’.

He was seeking a legal opinion on two questions. One: Did the search for al-Mihdhar have to be an intelligence investigation? And Two: If found, could al-Mihdhar be interviewed in the presence of a criminal agent? Dina Corsi contacted Sherry Sabol, an FBI lawyer at the National Security Law Unit NSLU, and Corsi relayed what Sabol supposedly said back to Bongardt.

In answering the first question: Corsi and Sabol agreed after 9/11 that Sabol had wrongly advised that the search for al-Mihdhar had to be an intelligence investigation. But whose fault that was depends on whether Corsi mentioned the salient facts of the case: the identification of bin Attash at Kuala Lumpur, and the fact that al-Mihdhar was with him there. Given her withholding of that information from FBI criminal agents, there is every reason to doubt that Corsi did tell her those salient facts. No documents were found after 9/11 showing how Corsi presented the case to Sabol, and there is nothing in the public domain about how Sabol remembers her consultation with Corsi. But this was a vital thing to investigate.

“He said he would be shocked if anyone in NSLU gave such advice…”

The advice given on the second question, whether a criminal agent could be present during an interview of al-Mihdhar, was a bone of contention between Corsi and Sabol after 9/11. Claiming to be relaying Sabol’s advice, Corsi wrote back to Bongardt: “If al-Midhar is located, the interview must be conducted by an intel. agent. A criminal agent CAN NOT be present at the interview [sic].” This clearly contradicts the law, and Sabol’s later testimony. The 9/11 Commmission Report said in an endnote: “The NSLU attorney denies advising that the agent could not participate in an interview and notes that she would not have given such inaccurate advice. The attorney told investigators that the NSA caveats would not have precluded criminal agents from joining any search for al-Mihdhar or from participating in any interview.”

The stoutness of Sabol’s denial that she said a criminal agent could not be present at an interview is reinforced by the testimony of the FBI general counsel, Larry Parkinson, to the 9/11 Commission. A memorandum of that testimony says:

When told that Dina Corsi alleged that NSLU had told her that no criminal agents could be involved in the search for the two men and none could participate in any interview if they were found, Parkinson said he would be shocked if anyone in NSLU gave such advice. He said there would have been no problem with a criminal agent hopping in on the search or participating in an interview. There was no FISA on these individuals so no internal wall would have been applicable.

Everyone seems clear on the law except Corsi. The suspicion has to be that Corsi was still working to make al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi’s arrest impossible, or if, by some chance, they were arrested, to make sure that their plans didn’t reach the highly motivated Cole investigators who would stop an attack.

In an endnote, The 9/11 Commission Report says, using Corsi’s alias in that report “‘Jane’ did not copy the attorney on her e-mail to the agent, so the attorney did not have an opportunity to confirm or reject the advice ‘Jane’ was giving to the agent.” I think it is reasonable to say that in noting this, the report was making more than just a note on proper procedure. The Report was saying more than just that Sabol should have been able to have a look at what Corsi represented Sabol’s advice to be, for the sake of total accuracy. Because this was a simple matter: could a criminal agent be at an interview or not? And Corsi put it in all-caps: “a criminal agent CAN NOT be present at the interview.” The unavoidable conclusion, the conclusion that I believe the Commission was hinting at, is that Corsi faked a critical legal opinion.

So the wall, the way Corsi used it, was not just a bureaucratic befuddlement that everyone would regret after 9/11. It was a deliberate lie to keep the alleged hijackers free.

Loose ends: late August 2001

After relaying the supposed legal opinion, Corsi ordered Bongardt to “stand down” from the search for al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi. In fact as Lawrence Wright tells the story in his book The Looming Tower, there was one final conference call in the fight over how the investigation should be conducted. On this call, Corsi told Bongardt to “stand down”, but so did “a CIA supervisor from Alec Station”. What was a supervisor from Alec Station doing in this call about what was supposed to be an internal FBI administrative matter? And the real question is: was this Tom Wilshere? Almost certainly, given how closely Wilshere was working with Corsi at this time. But whether it was Wilshere or not, it tells us that Alec Station’s protection of the alleged hijackers was still going on. A week after they told the FBI about them; in the high threat environment; with about two weeks to go before 9/11. One of Bongardt’s last comments to Corsi and the CIA supervisor about al-Mihdhar during this conference call was, “If this guy is in the country, it’s not because he’s going to fucking Disneyland”.

On August the 30th, eight months after the identification of Khallad bin Attash in the Kuala Lumpur photos, the FBI received a formal notification from the CIA about it. As the Justice Department Inspector General’s Report notes, “This is the first record documenting that the source’s identification of Khallad in the Kuala Lumpur photographs was provided by the CIA to the FBI.” This despite the fact that the source, i.e. the Islamabad source, was approved to be used by the FBI. And also despite the fact that Dina Corsi, an FBI analyst after all, was seemingly already aware of it for an indeterminate amount of time, and first mentioned it in the email to “Glenn” that she wrote on August the 22nd.

The notification was made at the request of Dina Corsi, and was passed to the FBI through a “CTC representative to the FBI” according to the Justice Department inspector general. That would be one way of describing Tom Wilshere.

The CIA notification told the FBI to get in touch if the FBI didn’t have the photos that had been shown to the Islamabad source. The source had been shown two of the three photos that were shown to Steve Bongardt. I hope you can see how important that is, because it means that if Bongardt had been shown the photos in which the Islamabad source had identified Khallad bin Attash, the Cole bomber, he would have seen that the other person in them was Khalid al-Mihdhar, whose photo Corsi had told him he had shown. Bongardt would have been able to point out the clear connection between the two men.

Amazingly, but I hope not too amazingly at this point, there is no record that this identification was passed to the Cole investigators before 9/11. The identification would have been a cause of great excitement to them. Given that Dina Corsi made the request, it was surely she who received the notification, and continued her normal practice of sitting on important information.

So, picture the following scenario, according to which Dina Corsi gives Bongardt all the information she has and he is entitled to, on the day she officially receives it.

Number one: on August the 28th, Steve Bongardt is sent the NSA cables linking al-Mihdhar to the Yemen communications hub and to the Kuala Lumpur meeting.

Number two: on August the 30th, Bongardt is informed that Khallad bin Attash was identified as being at the Kuala Lumpur meeting and is sent the pictures on the basis of which the Islamabad source made the identification. He immediately recognises that the photos are two of the three he had been shown at the June the 11th meeting, and knows therefore that the other person is Khalid al-Mihdhar; and therefore that Khalid al-Mihdhar was linked to the mastermind of the Cole bombing.

If it had happened like that Bongardt could have argued on unimpeachable grounds that the search for Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi should be a part of the Cole criminal investigation. And he would have caught them. On September the 11th, after the attack, Bongardt turned up leads that would have led him to the men within hours, and don’t forget the two men lived with other alleged hijackers.

Here is how the top White House counterterrorist official at the time, Richard Clarke, put it.

Clarke: If they had, even as late as September 4th [when Clarke attended a ‘principals’ meeting’ in the White House with DCI George Tenet and other CIA officials] told me, we would have conducted a massive sweep. We would have conducted it publicly. We would have found those assholes. There’s no doubt in my mind. Even with only a week left. They were using credit cards in their own names. They were staying in the Charles Hotel in Harvard Square, for heaven’s sake. We would have found them. If we had taken those pictures, and put them out on the AP wire, those guys would have been arrested within 24 hours.

John Duffy, interviewer: Have you asked George Tenet, or [CIA Counterterrorist Center chief] Cofer Black, or Richard Blee about any of this after the fact?

Clarke: No. Look at it this way: they’ve been able to get through a Joint House Investigation Committee, and get through the 9/11 Commission, and this has never come out. They got away with it. They’re not going to tell them, even if you waterboard them.

Clarke may or may not be bullshitting about the possibility of a public sweep. And he was not exactly one of the good guys, not unambiguously anyway. But about how easy it would have been to make arrests, he was right.

But what was the point of Alec Station telling the FBI that the two alleged hijackers were in the U.S. on August the 22nd? What was the point, on August the 28th, of Dina Corsi getting the permission of the NSA to tell the Cole criminal agents about al-Mihdhar’s links to the Yemen hub and his travel to Kuala Lumpur? What was the point of the CIA’s passing the identification of Khallad bin Attash to the FBI, on August the 30th? In each case, except the hijackers’ mere presence in the States, and that only happened by accident, the information didn’t get to the people who really needed it and could use it, the Cole criminal investigators. So what was the point? Given the timing, and what we know about the high expectation at that time of an attack, and also given the fact that we’ve been given no other real rational explanation, in the absence of other evidence, it is fair to say that all this passing of information to FBI Headquarters, but not FBI field agents, allowed the blame to be shifted from the CIA, and from specific CIA officials like Tom Wilshere, Richard Blee, and others more junior, to the FBI after the attack. “They were given all this information, and they did nothing!” That was actually the general opinion after 9/11. The FBI got the blame, and the CIA didn’t, which was fair enough only on the most superficial reading of events.

I ought to be clear here. The original decisions not to pass the various pieces of information, and the subsequent action of passing them on, were not a matter of turf wars between agencies and clashing personalities, the way Lawrence Wright and many others have portrayed it. Wright focuses on rivalry between the previous chief of Alec Station, the truly gross Michael Scheuer and an FBI counterpart of his, John O’Neill. All of that is a comforting explanation, because it means you can avoid the issue of intentional wrongdoing. It is a kind of common sense that lets CIA officials off the hook. But it does not answer the fact that as an intelligence official, if you withhold information, it’s because you want to make use of it, to do something with it. When al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi originally arrived in the States, you could say this was merely to monitor them, or perhaps to attempt to recruit them for use against bin Laden. But by the time that an attack was expected in the summer and autumn of 2001, if you haven’t got them off the streets yet, if they are still being used, if you’re doing something with them, it is either as operatives or stool pigeons in an attack. By common consent, this was a time of grave danger. So whose reputation was served by preventing the arrest of supposedly highly dangerous men? None of this was done in ignorance. As Tom Wilshere’s July 23rd email, saying al-Mihdhar would be involved in the “next big op” shows, as Richard Blee’s “they’re coming here” comment shows, it was done in the knowledge of the danger it was courting. It really does seem as if the most likely explanation is that they wanted that potential violence realised. If I am surmising what seems to me the ineluctable conclusion, I would nevertheless be all agog for the testimony, the facts, the evidence, that would prove me wrong. It would still at the most be evidence of criminal negligence and moral lunacy, far beyond what we’ve been told about in the comforting accounts. It just hasn’t been forthcoming in the past 17 years. And it’s more like a theoretical possibility, or someone’s naïve hope, than a realistic possibility.

The rookie’s goosechase: September 2001