The CIA’s Files on Ireland

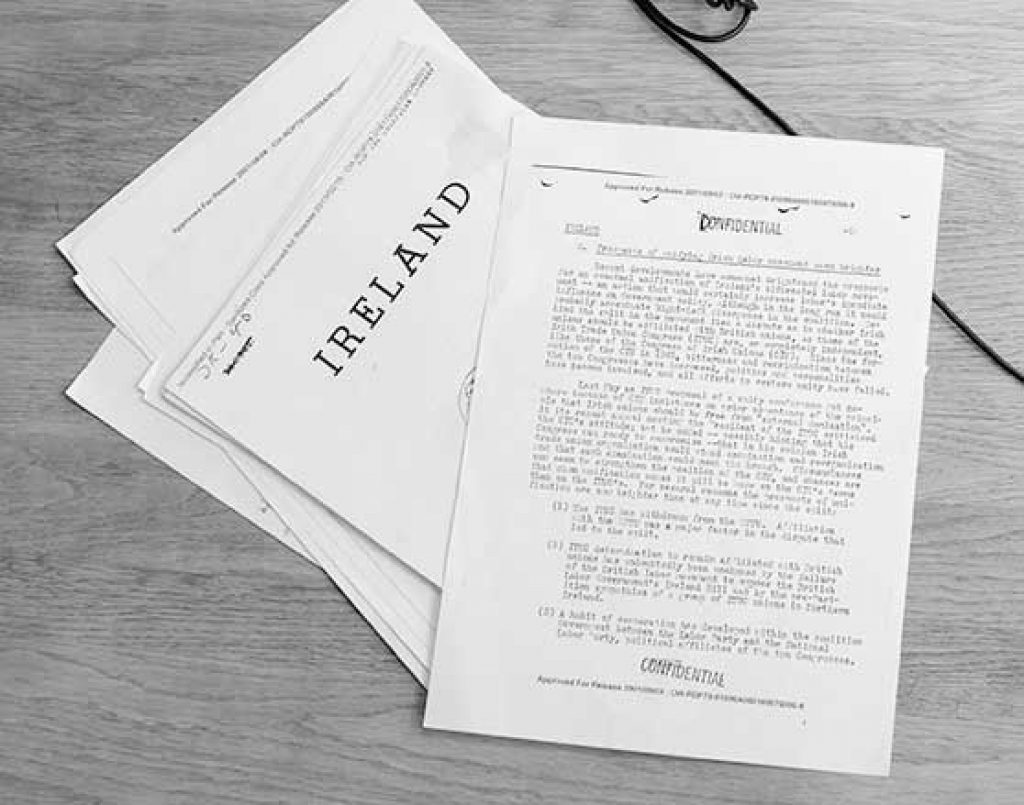

The Central Intelligence Agency has a publicly accessible database, called CREST, which stands for CIA Records Search Tool. CREST has a PDF of every declassified document of historical value produced by the CIA which is over 25 years old. CREST has existed since 2000, but for a long time it could only be accessed through four computers at an office of the National Archives in Maryland. A couple of years ago, the CIA responded to legal action seeking to make the material available online by saying that this would take six years. So someone called Emma Best started printing off every document on CREST for online reproduction. The charming thing was that the CIA didn’t charge for printing off documents at these computers, and as we all know, printing is expensive. The CIA caved, and since January 2017, CREST has been on the internet.

Out of the idlest curiosity I decided to have a look at what there was on CREST about Ireland. It’s not that I expected anything sensational, or anything juicy that had been overlooked. Depending on how you define juicy, I was more or less right. After all, in terms of international politics, Ireland just has been a fairly unimportant country. Here we are, floating comfortably between the US and the UK, a relatively comfortable berth in 20th century history. There is a tradition of other neutral countries, such as Sweden and Portugal, being places where clandestine operations did happen. But practically speaking, Ireland was just away from the battle lines of the Cold War. So that’s one factor explaining why juicy stuff isn’t there in the first place. Another part of the explanation is that declassified files tend to be analysis of publicly available information. They come from what the CIA used to call the Directorate of Intelligence, rather than the Directorate of Operations. It is reasonable to guess that the CIA has cables on intelligence gathering in Ireland: regarding Northern Ireland, for example, but also about ordinary contacts with politicians, in which an officer might simply get the same kind of information or perspective that an ordinary diplomat would get. But all that is precisely the stuff that’s not been declassified.

But the themes that arise in these analyses are interestingly revealing: about American foreign policy, about the CIA, and about Ireland. It turned out that even these analyses are small in number, so I am going to go through them in a roughly, but not strictly, chronological order, and let their themes reveal themselves.

Envisaging a hot war

The first significant document is titled simply, “Ireland”, with a publication date of 1st April, 1949. It’s 46 pages long, and was part of a series of Situation Reports regarding 48 countries which fundamentally were written up in hot response to the beginning of the Cold War. More complete National Intelligence Surveys were eventually due to be written, and there was some argument between the CIA on the one hand, and the military and the State Department on the other, about whether producing these Situation Reports was worth the bother. But it was going to take at least a year for the first of these Surveys to be published. “In view of this”, wrote the CIA officer overseeing the task, “it is desirable to have some coverage of world areas in event of unforeseen emergency”. That gives an idea of the urgency with which the CIA was treating the prospect that there might very soon be a hot war with the Soviet Union.

With that fear in mind, the first striking thing, in the Situation Report, is to see Ireland described in the bald terms of its potential military-strategic value. Here’s how it opens:

Because hostile military forces established in Ireland would be in a position to dominate lines of communication vital to the security of the United Kingdom and to develop air and submarine bases for attacks against North American war capabilities, denial of Ireland to an enemy is an inescapable principle of United States security. As an ally in an East-West war, Ireland would be a positive asset because it could provide sites for air and naval bases, sheltered by Britain’s air defences, from which strategic bombing, anti-submarine, and convoy protection operations could be facilitated. Although Irish neutrality in such a war would probably be tolerable, it could become necessary to utilize Ireland for these purposes under conceivable circumstances of sustained aerial bombardment or hostile occupation of British ports.

The Situation Reports were produced with the assistance of the various branches of military intelligence, and their advice is apparent in the Ireland report. Here’s the Air Force bit:

Its terrain and topography lend themselves to rapid construction of airfields which would be Invaluable as bases for strategic bomber attacks as far east as the Ural Mountains. Defense of such bases from air attack by European-based planes would be greatly facilitated by the need for such planes to cross the anti-aircraft defences of Great Britain.

And here’s the Navy contribution: “Naval and naval air bases in Ireland would extend the range and effectiveness of anti-submarine and convoy protection operations in the southwestern approaches to the United Kingdom and in the Eastern Atlantic generally.”

It is also notable that the planners were evidently envisaging a drawn-out and to a considerable extent conventional war with the Soviet-led Eastern bloc. In April 1949, the USSR was four months away from testing its first atomic bomb. The main method of delivering a nuclear weapon was by plane, rather than missile, and the weapons were less powerful than they became in the early ’50s, with the development of the hydrogen bomb. On the other hand, it was always thought most likely that a nuclear war would come after conventional battles in Europe, throughout the Cold War, right till the ’80s, so maybe all this is not surprising. The Situation Report actually says that while territory is what Ireland mainly has to offer, “its potential manpower contribution is not inconsiderable”.

NATO and Partition

Ireland, though, had been neutral through the Second World War, and did not join NATO, giving the reason that it could not join in an alliance with the United Kingdom as long as it included Northern Ireland, as long as there was partition in Ireland. The Situation Report goes into a surprising degree of detail about Irish history to account for Ireland staying out of NATO: from the Norman invasion in the 12th century, to the various Plantations and the Protestant ascendency in the 17th, to the Act of Union, and the Free State in 1922.

And then to account for the ability to remain neutral in the Second World War it mentions the British withdrawal in 1938 from the three ports it had retained under the 1921 Anglo-Irish treaty and the gradual severing of constitutional ties with Britain beginning in the ’30s.

But what were the prospects for Ireland softening on the Atlantic Pact, or at least participating in war if it came? The initial rejection of membership had happened because Seán MacBride, who as Minister for External Affairs was responsible for something like NATO, had simply written in response to a letter asking whether Ireland wanted an invitation, by saying there could be no membership as long as there was partition. MacBride followed up by lobbying the US to apply pressure against partition in exchange for NATO membership. The only hint of all this in the Situation Report is that John A. Costello’s inter-party government had “exhibited unusual optimism that the end of Partition may not be far off. This springs from a conviction that a united Ireland friendly to Britain would be more valuable in European defense plans than a divided Ireland”. It was assumed that the Labour government under Attlee in Britain at the time would be sympathetic to this. The CIA dismisses all this, correctly as it turned out, by saying, “At present there are no convincing indications that the end of Partition is imminent”.

It is worth pointing out that the Costello government was not unanimously and unbudgeably opposed to NATO membership even with partition. But the inter-party government was very weak: it required every party involved to retain a majority in the Dáil. MacBride led one of those parties, which had plenty of republicans in it. Until 1938 he himself had been IRA Chief of Staff. For reasons of parliamentary arithmetic, it would have been better not to tempt him and them. Seán Lemass, who was Taoiseach beginning a decade later, and a Fianna Fáiler to boot, thought we could join even with partition. Questions were asked of MacBride in the Dáil, about whether the matter was as simple as he was saying. So it really wasn’t as simple as he was saying. The CIA does not bring up these ambiguities, and just says, “Whether anything short of war would alter this attitude cannot be confidently estimated”, which was true as far as it went.

De Valera was out of government, but he was the first personality profiled

The Situation Report is accurate about the extent of the difficulty Partition posed. One of its most emphatic pieces of counsel is that

Opposition to Partition in the twenty-six counties is genuine, not artificial; constant, not occasional. If political parties keep the issue before the people, it is because they cannot do otherwise and continue to exist; on this issue, if they sometimes deride the effectiveness of opponents’ methods, they seldom question the sincerity of their motives.

What’s more, “the view is widely held that Partition was perpetrated and maintained by the British and can be ended by them”. It is interesting, because all these views are still reasonably widespread today. But reading them does still feel like reading ancient history, because they have equally come under severe question, because of the conflict since the late ’60s.

So NATO membership in 1949 was not on the agenda. But in an East-West war, Ireland, to quote the Report, “in all probability would not remain neutral”. De Valera was out of government at this time, but in an appendix on “Significant Personalities” his is amusingly and appropriately the first profiled. It says, “in the event of war, he is not likely to insist on neutrality if the conflict comes to be regarded as a ‘Holy War’”. It was not just Dev: “The attitude of the Church has great influence in Ireland, and the Irish would probably be deeply stirred on religious grounds by an East-West war”. So it was very possible that it would be all right on the night. Failing that, “bases in Northern Ireland would undoubtedly still be available”.

Neutrality: “intricacies of gloom and glint… fat on the flesh of your kin”

When the IRA comes up for discussion it is referred to as “a factor limiting internationalism”. To the extent that internationalism is a term for “joining NATO”, another such factor, in the CIA’s eyes, was Fianna Fáil, which it calls “the most neutrality-minded of the parties”. Its policies were said to be influenced by “intense nationalism” and “disillusionment with Big Power policies”, especially after 1935 when Britain and France stood by, connived even, during the Italian invasion of Abyssinia.

In fact, it is implicit in the Report that this disillusionment is characteristic of what it calls “Irish foreign policy” as a whole. “Always somewhat distrustful of Great Powers’ motives and possessed of a small country’s normal reluctance to become involved in their conflicts, the Irish were never convinced that moral considerations played a great part in Allied war aims”, it says, referring to the Second World War, and it notes that these factors were still present, even if attenuated by what are called “obvious reasons”, presumably meaning the Soviet Union’s being atheistic.

Since the Situation Report does not expand on this summary, even if it does show a certain comprehension of the Irish attitude to the Great Powers, it is worth interjecting briefly, provisionally, a little tentatively but also confidently, that distrust of their motives, and, after the War, of the Superpowers’ motives, has always been soundly based, a mark of sanity. And I believe that does extends even to the Second World War, seen not only as a necessary war, but as a well-intentioned one, partly because of the Shoah which happened during it – which relied incidentally on the fog of war. I like to point occasionally to Thorstein Veblen’s review of the famous book about the Versailles Treaty which ended the First World War, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, by John Maynard Keynes. Veblen chided Keynes for taking the treaty as “a conclusive settlement, rather than a strategic point of departure for further negotiations and a continuation of warlike enterprise”. The Treaty was an anti-Bolshevik pact. If Britain and France had wanted to ensure compensation and reparation for citizens and businesses affected by the war, they could readily have taken the German war debt, that is the debt owed by German government to its wealthy citizens, for themselves. They did not do so because it would have made more difficult their priority, which was “to reinstate the reactionary régime in Germany and to erect it as a bulwark against Bolshevism”. That is a fair description in 1920 of what happened over the next twenty years. There is an extra step, or maybe leap, from reasonable distrust and clear eyes, to not participating in a war against the fascist Germany resulting from this chicanery, that there is no time to get into here.

But this soundly based distrust of the Great Powers has a weakness, to the extent that it finds fuel in “intense nationalism”, the other factor the CIA said affected Fianna Fáil’s thoughts about the world. Anyway, the small number of declassified files from later in the Cold War reflect an incomplete Irish alignment with the Western powers, an outlook which the CIA recognised bore the decisive imprint of Frank Aiken, the Fianna Fáil Minister of External Affairs when Ireland joined the United Nations in 1955. A short profile of him in the 1949 Situation Report said, “By some accounts, he is very anti-British and anti-American”. An incomplete clipping from a 1958 article called “Ireland’s Foreign Policy” said the country “has taken a position which diverges sharply from that of other Western nations”, referring especially to Irish backing for representation of the Chinese communist government at the UN, and to a hopeful proposal for phased withdrawal of foreign forces – US and Russian – from Europe. Ireland was said to be “firmly anti-communist” but “the De Valera government is increasingly concerned with the inflexibility of the East-West power blocs and the threat of a general war”, it said, and Aiken was said to be mainly responsible for the “more aggressive approach”, which also included a “more active interest in colonial problems”, leading to a proposal for a UN investigation in Algeria, where France was fighting a brutal anti-colonial insurrection.

Incidentally, the phrase just mentioned, “the inflexibility of the East-West power blocs and the threat of a general war”, has the whiff of the Vatican about it. The Vatican at some points in the Cold War, as during the Cuban Missile Crisis, saw its role as a mediator between the blocs, counteracting inflexibility. The Situation Report had already noted a “special sensitivity to Vatican opinion”. So even if it was not the true determinant of Irish neutrality, one of the things that could be pointed to in justifying it was the Vatican’s perception of the Cold War.

Europe and the first Brexit referendum

I would be interested to know if calling Ireland both anti-Communist and anti-colonialist became a kind of pat Time magazine-style formula in CIA analysis, because a CIA paper sent to the White House in December 1974, in advance of Ireland’s first European Community presidency in the new year, refers to the Taoiseach at the time, Liam Cosgrave, as sharing “basic Irish opposition to communism and colonialism”. True enough, no doubt, even if the only the CIA could think of Liam Cosgrave as an anti-colonialist.

The only example this 1974 paper gives of an Irish stance that might in the broadest sense be called anti-colonialist is Dublin’s “going along”, as it says, with France on a pro-Palestinian position and voting with France to allow the PLO to address the UN General Assembly. Of course France was following its own economic interests in the Middle East in doing that. For example, around this time, it sold the Osirak nuclear reactor to Iraq.

That reference to “going along” with France is a clue to why exactly the paper, which is called “The Outlook for Dublin’s EC Presidency”, was most likely written. I read it three times before I formed a view as to what the paper is actually about. It tends to jump about a bit, going from an assessment of key personalities in the Irish government, to an outline of the broad outline of normal Irish external policy, to a passage about what it calls “The Northern Factor”. But it is in fact fundamentally centred on one topic. That is, how to make sure that France did not prevent the United States from learning things it wanted to know about European matters by exerting too much influence on Ireland during its presidency.

That might seem strange. Why would France being uncooperative be such a big issue? In historical context, though, it makes sense. For one thing, this paper was written at the request of Denis Clift, who was on the National Security Council staff at the White House. For another, the 1970s were a pretty chaotic time, for the international economy, and for relations between America and Europe. Under Nixon, who was president until August ’74, the US had abandoned the gold standard, making it impossible for European countries to redeem their dollars for gold, while also leaving it impossible for them to stop taking the dollars in payment. After all, if the Europeans only took payment in their local currencies, without reinvesting them in U.S. financial instruments like Treasury bills, the local currencies would appreciate unsustainably and ruin their foreign exports. The Treasury Secretary, John Connally, summed up this shock by saying the dollar was “our currency, but their problem”. Nixon topped this by intensifying exports to the Communist bloc. And the oil crisis, which hurt Europe more than the US, also helped nicely. In short, Nixon had conducted a trade war. Of a mind anyway to be independent under the influence of de Gaulle, France in particular at this time had reason to question how reliable the United States was. So did the rest of Europe. By the time Gerald Ford became president after Nixon’s resignation, it was time for a more diplomatic American approach, while being mindful of possible European backsliding, such as by information withholding.

The 1974 paper notes, as the Situation Report had too, that a “pro-French leaning” is a “constant thread of Irish foreign policy”, and that Ireland had agreed with France about almost everything since joining the EC. It notes that Ireland at that time was looking to the EC where previously it looked mostly to the US and the UK in its external relations, but also that there was potentially disagreement about how federal Europe should be, Ireland being all for federalism, while France, as it had been under de Gaulle, was more interested in a Europe of Nations. Garret Fitzgerald, Minister for Foreign Affairs at this time, is quoted as saying that since becoming an EC member, Ireland now had express a viewpoint about many more issues, and the ultimate reason for this was, “that when we seek to press the particular needs of this country we shall be listened to attentively and willingly”. In other words, there were plenty of opportunities for quid pro quo sleeveenery, and this would not necessarily be helpful to America.

When it came directly to assessing the state of play in relation to information flow between Europe and the US in 1975, the CIA assessment was that Ireland, as a small country with a seat at a big table, and for a few months at the head of the big table, naturally wanted to use the EC presidency “as the principal channel for US-EC consultations”, but was wondering whether Washington was interested in that while a small country was in the post, and whether information exchange would be reciprocal. France was actually in the presidency just before Ireland, and it is noted that Paris had sought to impose a total embargo on talking to Washington about the proceedings of some EC meetings, such as those of Asian specialists. Clearly, the battle for competitive advantage in international markets was not over. The paper says

The Irish [redacted] will be under pressure from Paris similarly to withhold information. However, their position is likely to depend on how seriously they think the presidency is being taken as a channel for consultations. At present the Irish are questioning whether Washington may not be more interested in consulting with the larger EC members than with the EC as a unit.

And then there is some information about the simple practical difficulties of Ireland in the ’70s holding the presidency: a small foreign ministry, few enough flights to Dublin. Normally, apparently, the foreign ministry of the presiding state would have set up an agenda for meetings on Asian or Middle Eastern affairs, and given briefings on topics of interest from a European point of view. But it was expected that there simply would not be enough manpower and expertise. And this was where the French had an opportunity to help, at a price, so America feared:

The other EC countries – particularly France – may offer to help Dublin in various ways. Only so much can be done along these lines, however, and to some extent help from an EC partner will also give that partner considerable influence over Irish policies and positions.

The paper does not explicitly recommend a policy, which after all is not officially the job of the CIA. It simply finishes up by saying that Dublin will be “extremely sensitive” to the attitudes of other EC members, but also to Washington’s. But it seems to follow from its analysis that if the White House wished to obtain EC information, and head off the risk of French influence on the Irish presidency, it would do well to treat the presidency as a serious means of communication with the EC, and also to pass on substantive information that way. And that would be in line with normal American policy anyway.

The last clues as to what inspired this White House-commissioned paper, and to how the problems it discussed were in fact partly resolved, is that three days after it was received, Ford and the French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing met over two days for a poolside summit on the French Caribbean island of Martinique, where incidentally Ford established a warm personal relationship with Giscard of the kind that French presidents did not have with either Ford’s predecessor, Nixon, or his successor, Carter. And the success of that meeting would lead, largely on the political initiative of France, to the first G7 meeting between the heads of government in the leading economies in November 1975. So France got a seat at an important table. By the way, that is not necessarily to say that the EC was not used as a means of communication and diplomacy. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find out how the considerations referred to in the CIA paper worked out. Ultimately, anyway, partly by means of the G7, which grew to include the president of the EC as an invitee anyway, and other talking shops like the OECD, the United States government prepared, with the ready co-operation of the other developed powers including France, the rejuvenation of America’s economic position during the rest of the ’70s. This concluded with a huge interest rate increase in the early ’80s, drawing much European finance, which solved, for that time, the US Balance of Payments problem.

“a British withdrawal would pose difficulties for relations with Northern Ireland…”

1975 was also the year of the first British referendum on Europe, when the UK stayed in by large majority. It wasn’t clear that there would be a referendum until that March, but, with a foreshadow of David Cameron’s travails, a renegotiation of Britain’s terms of membership had been going on since early the previous year, and the paper on Dublin’s EC presidency notes that

With the Irish economy still closely entwined with Britain’s, Dublin makes it a cardinal point not to espouse any policy contravening basic British interests. For its own as well as London’s benefit, Dublin has been pressing the French to take a more generous position toward the UK’s effort to negotiate more favourable terms for its EC membership.

Obviously Ireland is still pursuing a policy based on economic interest, probably with an additional perceived political interest on the part of the present Irish government. Anyway, that passage does show what an unusual time we are in just now, to the extent that a lot of Irish diplomatic energy is directed against British policy, or manoeuvring.

The déjà vu continues with a short “Staff Note”, essentially a page in a regularly produced bulletin. This note was published a couple of weeks before the 1975 referendum. Here is the note in full:

The government in Dublin has concluded that if London decides to bolt the EC, Ireland would lose more by pulling out than by staying in. The Republic will sustain a loss if the UK withdraws, but a recent Dublin survey suggests that the country’s annual GNP would only drop approximately $235 million if Ireland remains in, but $470 if Dublin withdraws with London.

Although the present Dublin government is in favor of staying in, a British withdrawal would pose difficulties for relations with Northern Ireland. The border between the two parts of Ireland would thus become an EC frontier, causing some serious political, as well as economic, repercussions. Nearly 10 percent of the Republic’s exports go to Ulster. The increase in tariffs on such goods, without the present free trade agreement with the UK, would add to Dublin’s overall drop in trade.

There have been indications that businessmen in Ulster are concerned about a possible UK withdrawal. One group visiting Brussels recently was told by EC officials that all outstanding loans to Northern Ireland businesses would be called immediately if London leaves the EC. Another group of local government officials visiting an EC capital were told that an independent Northern Ireland would not be excluded from membership if the UK or the Irish Republic did not object.

Kind of eerie. Except for the last sentence, everything has an echo today. And it is not really a mystery what the bulletins on the backstop are most likely saying these days: something much the same as this, just updated. But it would still be fun to see the briefings.

Incidentally, another part of the 1975 bulletin that note comes from is a note about public opinion in Denmark about the EC, and there is something else entirely redacted with the classification code 25X6, which is supposed to indicate that publishing the redacted part would cause serious diplomatic damage to the US. This is almost certainly about the UK’s EC referendum, and almost certainly it when the bulletin was declassified in 2001, it would not have caused the slightest diplomatic damage. It is just one of those things you find while going through these documents: that any hint that the US in many respects thinks of the UK as just another foreign country, as it demonstrably does, has to be redacted; even the most innocuous hint, such as the fact there was a CIA-produced national intelligence survey on the UK, like there was for every country. A small price to pay for a profitable trade deal.

Governing the world

A lot of the rest of the CREST files about Ireland is fundamentally news, small articles that could as well have appeared in an Irish newspaper as political reporting or analysis. And they are pretty random. My guess is that they were released as slim pickings in response to freedom of information requests. In chronological order: the likely result of the 1961 general election; Neil Blaney being a pain to the Taoiseach, Jack Lynch, and causing tension in government over Northern Ireland in 1969; Lynch being very likely to overcome a leadership challenge from Charles Haughey after the Arms Trial in 1970; the 1973 presidential election. I mention all this just because of the sense it gives of what hum-drum daily analysis and reporting is.

“There is no Catholic party as such, but all parties could so qualify…”

But there is another strand of reporting with which it is worth finishing our look at the analytical material, because it says something about what the CIA fundamentally is. This is its persistent concern with the form of economy, state intervention in the economy, property rights, labour rights, and how all these are represented in party politics.

In the 1949 Situation Report that we began with, for example, an important point relating to the structure of government in Ireland is that the right to own and transfer property is constitutionally guaranteed, and a law infringing that right would be struck down by the courts. And then there is a kind of marking of cards of the various political parties regarding economics and property rights. So that Fianna Fáil favours “a limited amount of state control of the economy and state assistance in the development of industry”, “[t]he wealthy and conservative elements” support Fine Gael, and Labour is the most trade-union conscious of the left-wing parties. The Catholic Church is noted as a conservative force in society, not just opposing communism but also nationalist revolt, and amusingly there is said to be “no Catholic party as such, but all parties could so qualify”.

It is not that the CIA imagined reds under every bed. For example, it dismissed the idea that trade unions or the left-of-centre parties Labour and Clann na Poblachta had been infiltrated by communists, and this at a time when, as it also notes, red scares were a winning tactic for Fianna Fáil. At this time, according to an article by Professor John Horgan, the American Legation in Dublin was reporting back to Washington that there was a concerted communist effort to infiltrate Irish newspapers. Maybe that was just because the diplomats were idle and stir-crazy. The Situation Report just notes that, “Communism has little appeal to the Irish” for religious reasons, “offers no conceivable threat to the State”, and mentions the name of the leader of the “minute Communist element”, Sean Nolan; which brings to mind the way the State Department cables leaked by Wikileaks had the names of all the Dublin imams.

What is striking is simply this need to know, to keep tabs on, all economic developments. There is a CIA briefing on the prospects for a unification in the Irish labour movement. Interestingly, it refers to a “brightening” of these prospects, and that adjective becomes understandable when you learn that it had become somewhat more likely that one of the trade union congresses would break their links with British unions. This would be a move away from cosmopolitan influence, on the whole a good thing for business, and was certainly being sought by conservative elements of society, including Fianna Fáil.

All of this is not such a big deal, it might be thought; it was Ireland, and after all, nothing happened. But if they were keeping watchful tabs on Irish trade unions, political parties, social institutions, they were doing so everywhere else too, and for a reason: to protect, and expand, the interests of American capital. In those places – Syria, Iran, Guatemala, Iraq, Indonesia, just to take us through the 1950s – where CIA-backed coups happened, there were disasters. There is indeed the non-trivial 20th century fact that Marxism-Leninism was a disaster, and in protecting American capital, the CIA was fighting against it, as well as against independent-minded governments which had their ups and downs. But the point is that if we attempt to construct in our time a more just, and pacific, social life, it will not necessarily be any better received.

A hint of an operation

It is unfortunate that there is no verifiable material about operations in Ireland in the CREST archive. Instead, when the archive was put online, Irish newspapers had to lead with the sexy story of something that sounded like an operation. What happened was that the CIA had declined to answer when asked whether it had assisted an IRA gun-running attempt in 1981. At trial, the five smugglers had presented an argument in their defence that the undercover FBI agent from whom they had bought weapons had in fact been a CIA informant, and that the smuggling had happened with the knowledge and approval of the U.S. Government, which was concerned that the IRA should not turn to the Eastern Bloc for weapons. Simply because the CIA does not present a defence in its own online archive, this story gains a superficial plausibility, which the newspapers did nothing to counter.

Now, it is plausible, in fact likely, that at various junctures during the conflict in Northern Ireland, that the CIA made some form of direct contact, however clandestine, with armed Irish Republicans. After all, it is apparent from the declassified files that the CIA had at least one eye on Soviet contact with Republican paramilitaries. A photocopied Sunday Telegraph article from 1975 records the arrival in Dublin of Vladimir Kozlov, ostensibly a correspondent of Tass, the Soviet news agency, but thought by British and Irish security officials to be “a member of the notorious Department V of the K.G.B., which is responsible for assassination and sabotage”. He was alleged to have made contact with the INLA, which had splintered from the Official IRA. In these circumstances, the CIA would have regarded sticking their oar in as merely part of the job.

But still, there is a high likelihood that the gun-runners’ defence was a try-on: CIA informants do not necessarily proclaim government motives, or introduce themselves honestly. But the defence succeeded, and the five men were acquitted. As the journalist Ed Moloney has written, it may be that the jury bought an unlikely story, or acted politically at a time when the Hunger Strikes were world news. And even if the undercover FBI man had a CIA connection, it would not mean the CIA was facilitating gun-running. As Moloney points out, in the early ’80s, under pressure from the British, the U.S. Government had started to target and interdict IRA gun-smuggling as it had not done in the ’70s. A CIA informant could have been involved in such an operation.

Apart from that, there are a couple of letters responding to interested Irish-American organizations by declining to comment about whether the CIA was working in Northern Ireland in the 70s and 80s. Pragmatically speaking, there is confirmation that of course something was happening in the form of a copy kept by the CIA of an August 1970 article by Proinsias Mac Aonghusa, most likely for the Sunday Press. “The Central Intelligence Agency’s operation in Ireland has increased considerably in recent months and will be expanded still further in the coming weeks”, it begins, and he notes later on that

It appears that the principal C.I.A. man in Ireland is not attached to the Embassy at Ballsbridge but is a former U.S. diplomat well known in Dublin society. He stood me lunch once and I often wondered why; now I know.

I pick out those parts of the article because there are hand-written tick marks beside those passages, as if, maybe, to say that Mac Aonghusa got these things right. The article also records that he had seen, “[b]y chance”, he wrote, “documents giving certain information” about this operation, which named that principal CIA man and others. Now, the idea that he had just chanced to see some CIA documents lying around is extraordinary, and can be confidently ruled out. For what it may all be worth, the rest of the article records that the expanded operation is still small, with not much money being spent on it, and that the reason for it is “of course, the disturbed state of the country and the possibility of violent changes in the structure of Government and society”. It is striking, however, that no republican faction, neither the Official nor the Provisional IRA, is ever mentioned in the article. Instead, it notes that one CIA asset who regularly travelled to Ireland, “keeps a close eye on the Universities and provides the most detailed information about professors and lecturers”; that the staff at UCD were considered “more revolutionary-minded and more dangerous to the status quo” than Trinity College staff; and that the asset was in touch with student bodies, but “his main mission is to keep an eye on teachers”. Things end on a cheery note: the operation does not mean that that the U.S. “plans an assault on Ireland or proposes to intervene in the event of revolution”:

Washington simply wants to be accurately informed of all that goes on and to have that information intelligently evaluated. I have the names of only a handful of C.I.A. agents and regular contacts in Ireland but if they are all of the same impressive calibre Washington is getting good value for its money and it really knows what is going on here.

Again, the idea that Mac Aonghusa – a softcore Irish republican incidentally – got his hands on the names of a number of CIA officers and assets, by accident, cannot be believed.

Proinsias Mac Aonghusa’s archive is at the James Hardiman Library in NUI Galway, seemingly in an unindexed state, and it would be nice one day to get there and see if I can find out if there are any hints as to the article was based on. In the meantime, it is impossible to arrive at a final answer about the article’s significance. But here are a couple of possibilities.

The first possibility is that this article in the Sunday Press was a form of limited hangout. Limited hangouts were defined by the former CIA officer Victor Marchetti as “admitting – sometimes even volunteering – some of the truth while still managing to withhold the key and damaging facts in the case.” He added that the public “is usually so intrigued by the new information that it never thinks to pursue the matter further”. One argument I can think of against the idea that it was a limited hangout is that there was no sufficient clamour for information about possible CIA operations in Ireland at the time. But there was some curiosity: for example, Conor Cruise O’Brien, a Labour TD at the time, wrote about it in his political diary in July 1970, a month before Mac Aonghusa’s article, and later published it in his book States of Ireland. In the diary he wrote that the CIA might have been able to work with the Haughey/Blaney wing of the Provisional IRA, if the Officials were ever to turn for help to the Communists, though he sensibly added in the book that he had no evidence of this and “would not attribute any major significance to such a factor”. After the article, if someone wanted to know whether the CIA were up to anything, there was an answer already published, without reference to the substance of the operation.

The other possibilities, perhaps more plausible, were mentioned to me by Tom Secker, when I asked his opinion. These are that the article was a form of communication between intelligence agencies: either that the CIA was thumbing its nose at the KGB, or letting British intelligence know it was operating in Ireland, without going through official channels, or – as an outside chance – that British intelligence “let the CIA know that they knew what the CIA was up to, as a warning to back off MI5’s turf”.

The operations side of things remains a black box to this day. That is a pity, but in fact the analytical material is quite interesting enough.